How to read Pitch Deck. Part One

Without a pitch deck, no conversation between an investor and a startup is concluded. How well you read the pitch deck directly determines the choice of a successful deal.

Everyone who has heard the word startup has definitely listened to another word: pitch deck. Venture capitalists get tons of e-mails from teams asking them to look at their products. Whether they will get the money depends directly on the quality of the presentation. To choose among the variety of beautiful slides that are really worthwhile, an investor should learn to understand the enticing numbers and words on his screen.

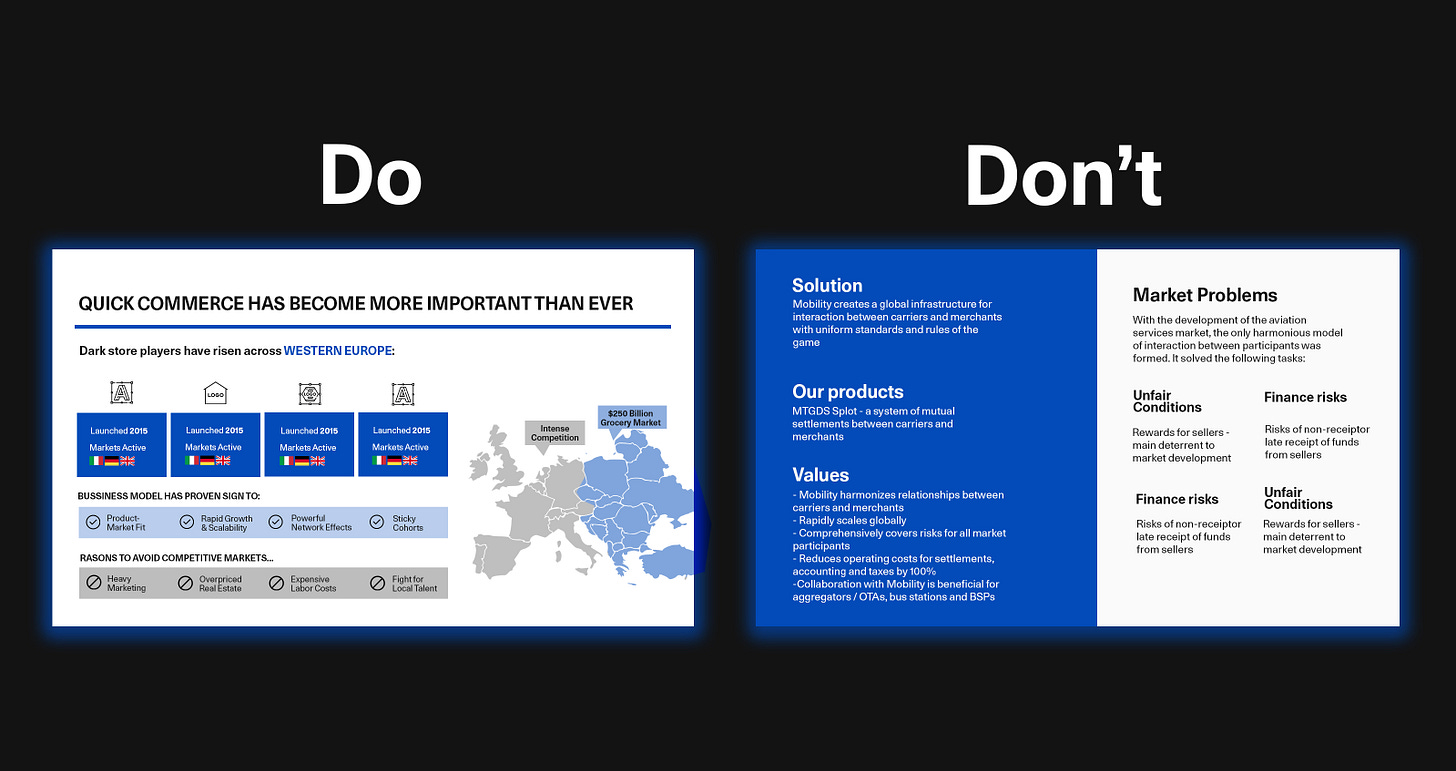

How to make a competent pitch deck is no secret. A founder can effortlessly find gigabytes of templates and successful examples on the Internet. Nevertheless, not everything is that simple. Otherwise, we would meet several unicorns even in the store's bread line. Time after time, startups make mistakes that lead to a loss of interest from investors. Our interest. The reasons vary from spelling and layout errors to attempts of withholding certain information about the company. Yes, pitching is not always a conversation between two gentlemen. Sometimes startups resort to juggling numbers and blowing dust in our eyes. An investor should be able to look through this fog and ask the right questions.

Risks we are struggling with

Venture investments are fraught with high risks. The task of the founder is to dispel them or, at least, mitigate them. While watching pitch decks, we mentally look for a sedative. We want the startup to convince us that the idea and product will work and that there is no need to worry. What exactly do investors care about? The team, the product, its innovativeness, the launch, and go-to-market strategy. So, we want to make sure that:

The startup team is experienced and professional (team risk).

The team has found a customer need and a solution to that need (product risk).

The team can build the intended product (innovation risk).

The team has a clear strategy and plan for scalability (launch risk).

Customers will like the product and be willing to pay money for it (go-to-market risk).

If the pitch deck makes us hesitant, it's a bad presentation or startup. For the investor, there is no difference. Next, we'll look at these points in more detail. Each of them has nuances that an investor should pay attention to.

Pitch deck structure

Pitch decks are not a place for experimentation. Decades later, the venture capital and startup world has standardized presentations. In the early stages, it consists of the following slides:

Problem

Its solution

Team

Market

Competitors

Traction (optional)

Strategy

Where the money will go

The list is not exhaustive and may include additional material, like press mentions. The order of the slides is not crucial, but must remain logical. For pre-seed, the absence of traction is forgiven. Everything else is mandatory. A pitch deck has 10-15 slides at most when you first meet them. Startups usually have an extended version of the presentation, essentially the same structure but in more detail. Pitch decks for later stages and IPOs will be skipped in this material. Let's start with the basics.

Problem

Every startup starts with an idea. This is the most lyrical part of the pitch deck, where a founder discusses the reasons for creating the product. Maybe the founder overhears a problem others are facing. Perhaps he encountered the trouble personally. Whatever that reason is, it should be based on data. In other words, the startup must show the existence of demand. Often, founders think there is demand when there isn't. But you can't get very far on intuition alone. It's a mistake to believe that the difficulty we personally encountered is widespread. Perhaps it is widespread, a solution has long been found, but we simply haven’t noticed it.

Ideas for a product don't exist by themselves. They are connected to the real world and are sometimes right under our noses. You do not create a startup for the sake of self-expression, but to solve a specific problem for specific people. Some studies say 90% of startups fail. One of the key reasons: there is no demand for the product because of a misunderstood market. For example, here's last year's data from CB Insights. It was the same ten years ago, take our word. From how it looks, the situation is going to stay that way. The last thing investors want to do is to get involved in a knowingly losing business because the roots of future failure come from here.

What should an investor pay attention to? Storytelling and proof of demand. The startup either has data from public sources or independent research – customer development. A simple telephone survey, a questionnaire by mail, or verbal feedback at an exhibition will help. Such events benefit not only product development, but also in determining the market. The better a startup thinks through the first stage, the better all the others will be. You can get the first orders and minimal traction if the need is found, even with a prototype in hand. The market will react quickly to the pain point and be willing to pay for a non-ideal product that solves the problem here and now.

Storytelling is another good indication of a founder's involvement in a product. A startup built on mercantile considerations will lose to a startup based on a personal problem. For example, a future founder is a diabetic. He had a good job, and life was going his way, but suddenly, his diabetes gave him a complication. The prospective founder had no idea that one of the results of the neglected disease was amputation. And so it happened. After this incident, he decides to help other diabetics around the world not to make their own mistakes. Thus begins the story of a startup developing a mobile app to control diabetes and prevent complications. Now compare that story to another. A would-be founder encountered an entertaining statistic on the Internet with the number of people suffering from diabetes. “Shouldn't we make money off them?” he thought. Investors would agree to give funds in two parallel dimensions where founders don't overlap. But if they had to choose, they would prefer the first one.

Not all stories are that dramatic. But remember: don't discount the personal attitude of the founders toward their child. This is especially important in the early stages. We'll talk about the team, though.

Solution

So, we have learned about the problem. Now it's time to learn about the solution that the startup offers. This is a voluminous block, which we will break down into three parts: the technical side, unit economics, and the business model.

In pitch decks, you will find a variety of technologies: from marketplaces and diapers to artificial intelligence and medical devices. All we have to do is get some basic information about the product. What is it? Is it a program or a device? What does it look like? How does it work in a nutshell? How hard is it to copy? The investor should remember the product category. This will help in assessing the competence of the team. Don't dwell on this part in detail. We are primarily interested in the money. It is up to the CTO to worry about the performance of the gizmo. The investor should be the last to go into the technology.

The point about technology is noteworthy because it is here that startups start to fudge their brains, substituting “innovation” for business. After releasing another piece, some journalists are sincerely convinced that the Pulitzer Prize is already in their pocket, and the text is at least genius. Young startups are experiencing a similar upheaval. The founder is relentlessly talking only about the product, going into every possible detail. At the same time, the business is moved to second or third place. This is a big mistake. For the most part, an investor doesn't care where to invest money: FoodTech, SaaS, children's toys, or pet radios. All that matters is that technology makes money. Pay attention to the concentration of such information in the pitch deck. If you can't see any business behind that wall, that's a cause for concern.

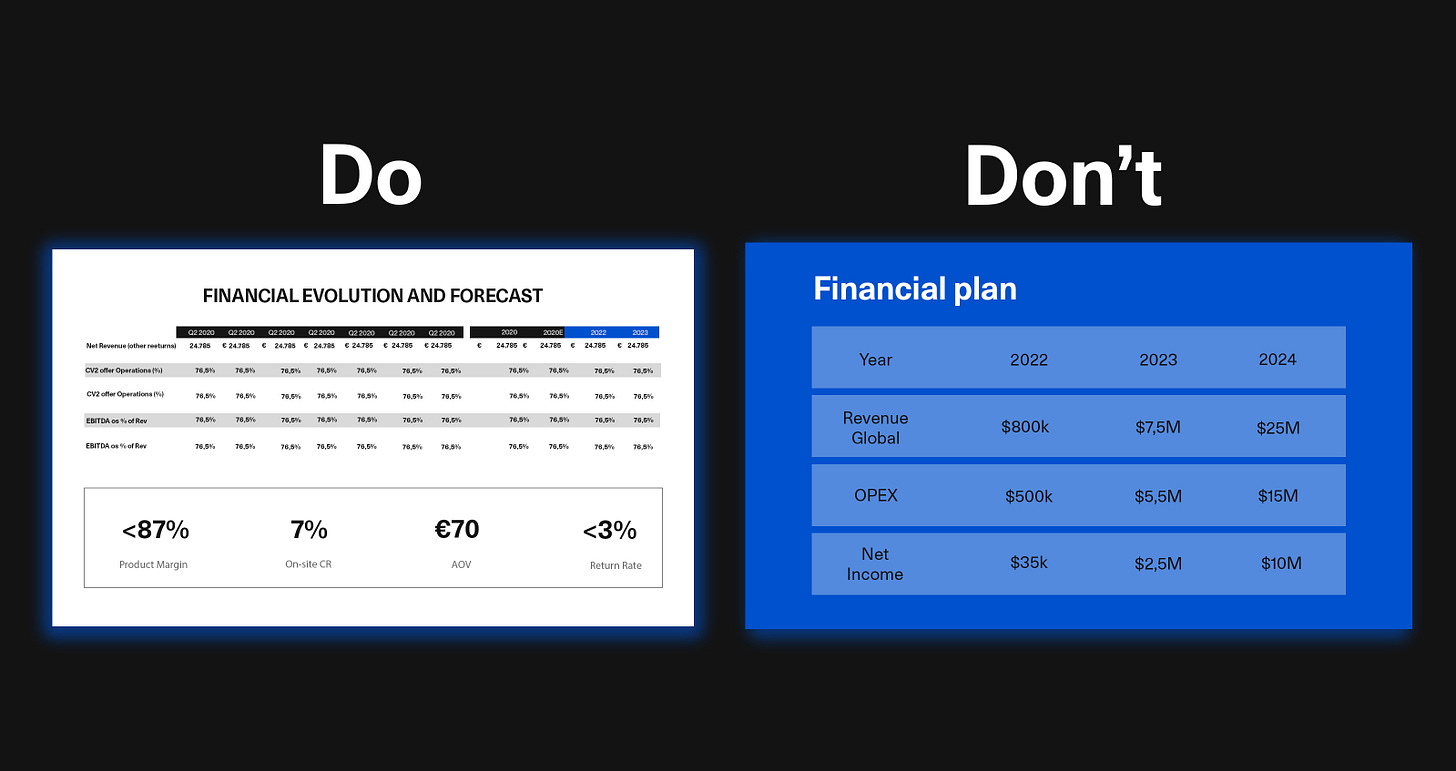

Unit economics is a set of metrics and indicators of the economic feasibility of a product. In other words, what costs does a startup incurs, and how much does it earn per unit, where a unit means goods. For example, one license, if it is software or one device, if it is hardware. Beginning investors face difficulties because it may be challenging to understand the terms and figures. Cost of revenue, advertising and per-client costs, CAC, LTV, MRR, ARR, ROI, AOV, margins, EBIDTA, and a host of other characteristics that a startup juggles require close attention. I bet those are the slides that take the longest to look at. Moreover, note that each startup could have particular metrics to be more essential, introducing even more confusion. We'll devote a separate issue to unit economics, while this article will only draw your attention to one thing. There should be unit economics. We understand your bewilderment, but startups do pretty well without it in their pitching decks. That's a massive mistake for the young prodigies.

And finally, we come to business models. Investors do not doubt the ability of startups to create products. But then, how to sell it all is a big question. The business model tells precisely how the startup is going to make money. In the local lingo, that sounds like monetization. Each startup can have its separate business model, even in the same category. The simplest example is a car dealership. The first one sells cars, the second rent them out for an hour, and the third decides to intercept customers with lucrative installment terms. Business models give room for imagination and allow newcomers to outsmart veterans with new ways of selling goods that turn out to be more effective than established ones. It is unlikely to be able to memorize all the existing business models for each individual area. Still, with experience, you will learn at least superficially to understand what works, doesn't, and could.

For example, we have a portfolio company, Coterie, which produces baby diapers. What business model would you recommend and consider worthwhile? Sell products through large retail chains or own branded outlets directly in maternity and children's hospitals? Sell in small bundles on a pay-as-you-go basis, or charge a year in advance? And what if you offer customers a monthly subscription with automatic delivery of a fresh batch of diapers once a week? Wouldn't the delivery be too much of a blow to the unit economics? That's the question the startup has to answer. The business model is in the top three, along with the team and the market. Now let's talk about them.

Team

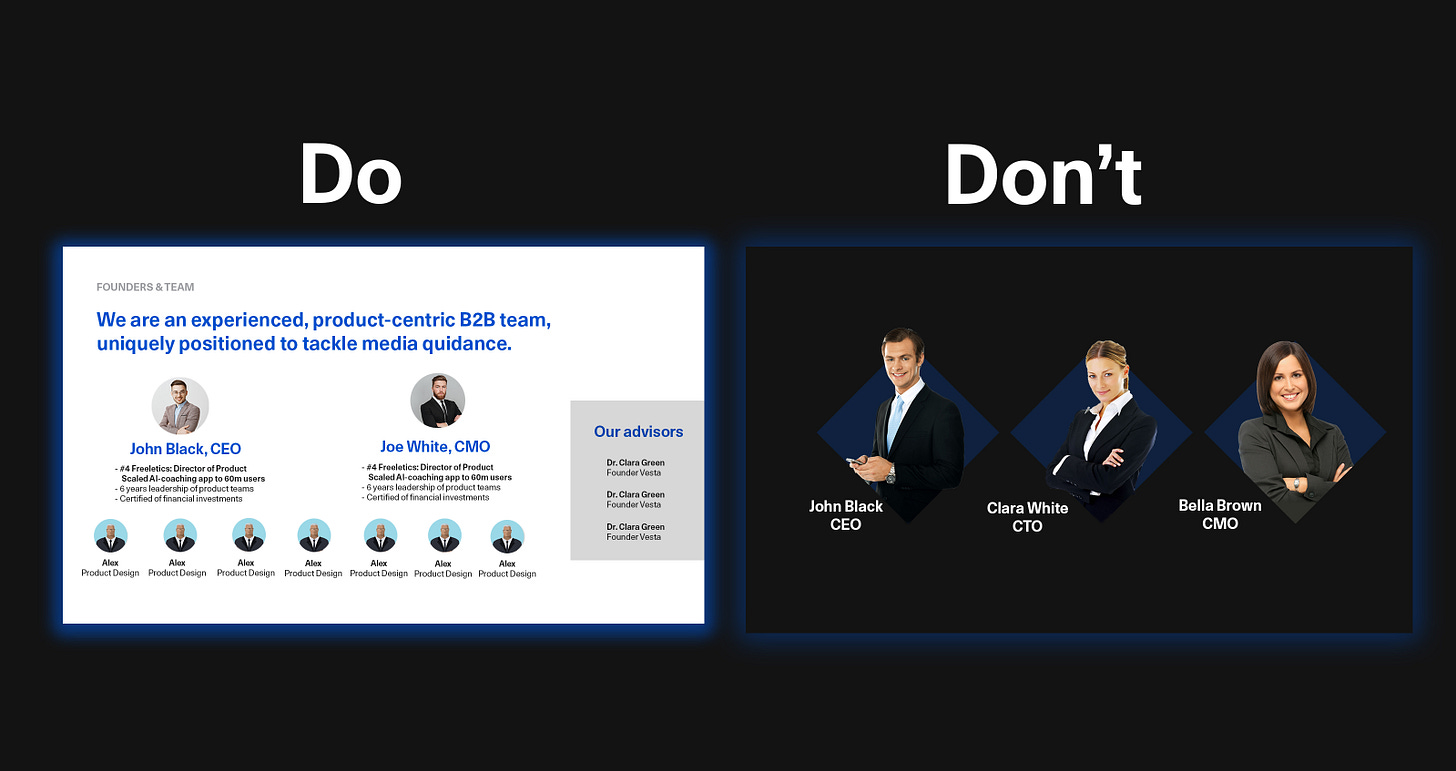

You should choose the former between a good team and a mediocre product. A good team will eventually be able to bring the product to fruition, whereas a bad team will probably ruin it. In the early stages, the team is the principal capital of the startup because besides itself, hypotheses and MVPs, there is nothing else to offer. In turn, management does not play such a significant role at later stages. Who will take over the established processes is a purely formal question. The management of a young startup, on the other hand, has to build the foundation from scratch, which means there are corresponding requirements. When viewing the slide with the team, pay attention to the staff, past jobs, competencies, and shares.

The size of the team means the ability to handle a complex and complicated product. It is impossible to say precisely how many people there should be in each individual case. Instead of numbers, look at the composition. Suppose no one else is on the slide except the CEO and the sales department. In that case, it's worth asking a logical question: who does the product development? The opposite situation is also possible when there are numerous developers but no marketing. The startup team has to be balanced and ready for the full launch of the product on the market: from strategy to development, advertising, and work with clients and partners. Ask how many people are full-time and how many of them are freelancers. The more people employed full-time, the better, and vice versa. If key employees do something half-time, the result will be the same. Full-time increases the likelihood that a team member won't quit at the most inopportune moment and devote themselves entirely to their work.

A separate case is top management. Ask tops if the presented project is the only one they lead. Founders may work in several startups at the same time, which reduces their involvement. Suppose this startup is just one of many for them, something like a backup. In that case, you shouldn't take such a project seriously, either. Oh yeah, and ask where they got their first money from. If founders aren't willing to risk personal money, why should you?

Remember how we asked you in the previous section to remember the product category? Suppose a startup's product is based on artificial intelligence. In that case, it means there must be specialists in the team with the appropriate experience. We repeat a similar comparison in other cases as well. HealthTech needs doctors, LegalTech needs lawyers, and Robotics needs physicists and programmers. If a startup pitches you a FinTech product without a single economist on the team, just politely pat the founder on the shoulder. Business models and the market are undoubtedly important, but the final product must exist and work as it should.

Let's finish this part with the question of shares. If the founder owns the startup alone, that's bad. If the stake is highly fragmented, that's bad, too. The concentration of power, on the one hand, speeds up management decisions. On the other hand, you risk losing the startup due to the mood of the founder. Fragmentation of a stake among many people represents another extreme case. The startup will remain manageable even in the case of dramatic situations with one of the top managers. However, executive decision-making is significantly inhibited because everyone wants to do things their way. This can drive the startup into a blind corner and cause conflicts within the team. Two or three people would be the optimal solution. Investors are attracted to a strong leader.

Market

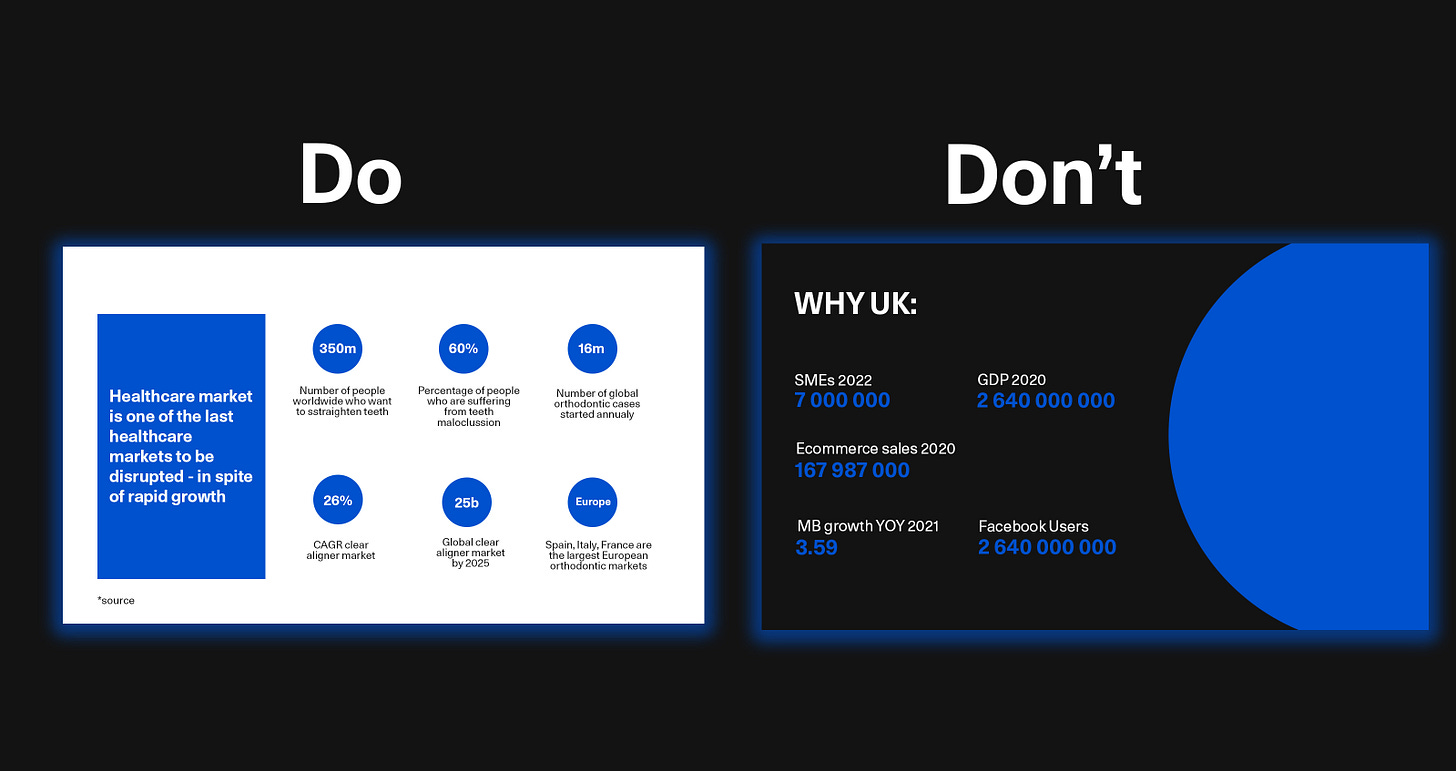

We are only interested in two characteristics of the market: the volume and the share that the startup plans to capture. The bigger the market, the better. More specifically, aim for the minimum figure of $1 billion. However, there may be exceptions.

It is important to note that market size affects a company's valuation and scalability. The larger the market, the higher the company's valuation and the more likely it is to make an exit. Scalability allows a startup to grow for a long time within the market. It is only vital that the market has room for that growth.

A startup's share is linked to the size of the market. Let's give an illustrative example. There are two startups, each intending to take 1% of the market. This may not seem like much to the novice investor, but don't be too quick to give up on the realists. The first team has chosen a $1 billion market and will end up with a 10 million share. Meanwhile, the second team chose a $10 billion market and will end up with a 100 million share.

At the same time, venture capitalists appreciate small but unoccupied and new niches that are just gaining momentum. Think of the hype dedicated to metaverses, NFT, and other fads. Some startups may enter the emerging market and take over one of the dominant areas. Such projects are rare because founders need breakthrough technology and an equal breakthrough flair. Here the ball is in the investor's court. Whether he wants to get involved in this money venture or not.

As a rule, be skeptical of projects that prophesy to break into the market and take large shares. But if they have insider information and reliable data, it's worth considering. Profitable markets are likely already occupied by competitors, which can't be dealt with at once. And now that we're talking about competitors.

Competitors

The slide begins, as usual, with the manifesto – our product has no analogs. As an alternative – we have no competitors. This is terrible news for the investor because the lack of competitors indicates one of two things. The startup either hasn't done its niche research homework or created a product no one wants. The chances of coming up with something unique exist, but they are minimal. Moreover, there is a difference between working in an existing market and creating something entirely new. The second, in addition to the high risks, requires a capital investment of time and money, which few people will go for. It is better to play it safe and offer the market an understandable product, but better than others.

Investors expect from a slide about competitors above all honesty. A startup doesn't have to be different in everything. A few killer features and working monetization are enough. This is where we come to the traction.

Traction

Traction refers to the money the startup has earned or is earning. At the pre-seed stage, there may be no such slide due to the age of the startup. Starting at the seed stage, it is mandatory. The traction answers the central question of the investor – where is the money? All the talks about the team, business models, market, and so on are expressed here. Traction is the proof of the viability of the startup. Guarantee that it can make money.

Demonstrating such a slide by a founder automatically raises the startup's level in investors' eyes. Now we are dealing not with hypotheses, but with a working business. This is an excellent time to talk about investments and prospects.

Strategy

While the share is inextricably linked to the market, the markets are linked to strategy. The slide about strategy talks about the startup's plans to enter new markets. This is called scaling. A startup that can't scale is bad. Scaling is one of the most important characteristics of startups because their products are created with global application in mind. You shouldn't expect a coffee shop near your house to expand internationally. But for startups, it is a matter of survival.

Where the money will go

Let's finish our talk about pitch decks with the final slide about the startup's plans to spend investor money. As with the team, look at the balance of spending. Spending items should include both development and promotion. A strong bias in one direction can be alarming. It is bothersome when some expense items are missing altogether. It should not be that way.

To sum up

In conclusion, any pitch deck slide is a test of trust. You, as an investor, cannot find out and control absolutely everything. Eventually, you have to trust the team. And if that's the case, track down reliable people first, and then look for technology.